In 1914, a doctor practicing near the Brooklands racetrack in England first correlated the relationship between motorcycle accidents and serious head injuries. Dr. Eric Gardner went on to invent the first purpose-built motorcycle helmet. It wasn’t until two decades later, when a head injury resulting from a motorcycle accident took the life of Thomas Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, that the first serious studies were conducted into the efficacy of motorcycle helmets in reducing the severity of head injuries. Hugh Cairns, Lawrence’s attending doctor and a leading neurosurgeon, used his findings and influence to ensure that helmets would become obligatory equipment for British Army Signal Corps riders going forward.

Early helmets were mostly constructed from cork, leather, and sometimes wood, and remained so until post-war developments in synthetic materials lead innovators such as Hirotake Arai to develop an entirely new design. Arai, a keen motorcyclist, had retooled his family hat business to produce safety helmets for construction workers. Applying the same manufacturing techniques, he began making and selling the first Japanese motorcycle helmets in 1952. They were made from a fiberglass resin outer shell lined initially with cork, and later, expanded polystyrene (EPS).

Seven decades on, motorcycle helmets, along with a multitude of international standards, have evolved exponentially, as has our understanding of science. Nonetheless, the infinite number of variables existing in a real-world crash ensure that even the most sophisticated models used to gauge a helmet’s ability to absorb an impact will remain controversial. While tests aimed at appraising shell penetration, peripheral vision, and the strength of chin straps lend themselves more readily to laboratory observation, governing bodies are forced to compromise in the face of producing practical, repeatable tests that accurately simulate impact absorption.

An effective helmet design aims to minimize the energy reaching the wearer in a crash, and since much of the testing involves dropping helmets from a given height onto an anvil, passing the resulting standards can be as simple as thickening the EPS layer in all the right places. Arai argues that the resulting helmet would no longer possess the overall strength and durability afforded by a sphere and ignores the role a helmet plays in redirecting and absorbing energy. In the same way a stone can be made to skim across a pond, a round, smooth helmet will glance off a surface, redirecting energy away from the wearer.

Arai’s design philosophy first accepts that practical limitations on a helmet’s size and weight restrict the volume of protective EPS foam it can contain. Inevitably, helmets can’t prevent all head injuries. But, with the understanding that safeguarding a rider’s head goes far beyond meeting the demands of governing bodies, Arai applies the “glancing off” philosophy to design helmets that reduce the effect of impacts on riders’ heads. Given that most impacts are likely to occur at an oblique angle because motorcyclists are moving at speed, Arai’s design aims to maximize the ability of a helmet to redirect energy by glancing off an object. The design is a function of shape, shell strength, and deformation characteristics that absorb energy along with EPS.

Arai collects crashed helmets for analysis and data collection, and uses the information to continually refine their helmet design.

Arai has developed and refined its approach through decades of evaluation and experimentation. Its helmets are round and smooth, and any protruding vents or airfoils are designed to detach on impact. The shell itself must be strong and flexible, but it must not deform too quickly or it will dig in rather than glance off. Arai uses multiple laminated layers combining glass and composite fiber to produce a very strong but lightweight material, and areas of potential weakness at the helmet’s edge and eyeport are reinforced with an additional belt of “super fiber.” Arai says its shells can withstand much higher abrasion than what is mandated by standards tests, and in doing so, can retain its energy absorption properties for a second or third impact.

While glancing off can redirect energy from the impact, a high-velocity crash may also require a helmet to absorb and distribute impact energy. Arai’s proprietary one-piece, multi-density EPS liner is made up of different sections of varying densities corresponding to the adjacent shell surface. This helps maintain the helmet’s spherical form and enhances its ability to glance off. In the case of a crash involving a slide along the ground and into an object, such as a curb or barrier, Arai’s helmets are designed to deflect the initial impacts with the ground with minimal shell deformation, saving its absorption properties for the rapid deceleration caused by impacting the object.

While glancing off can redirect energy from the impact, a high-velocity crash may also require a helmet to absorb and distribute impact energy. Arai’s proprietary one-piece, multi-density EPS liner is made up of different sections of varying densities corresponding to the adjacent shell surface. This helps maintain the helmet’s spherical form and enhances its ability to glance off. In the case of a crash involving a slide along the ground and into an object, such as a curb or barrier, Arai’s helmets are designed to deflect the initial impacts with the ground with minimal shell deformation, saving its absorption properties for the rapid deceleration caused by impacting the object.

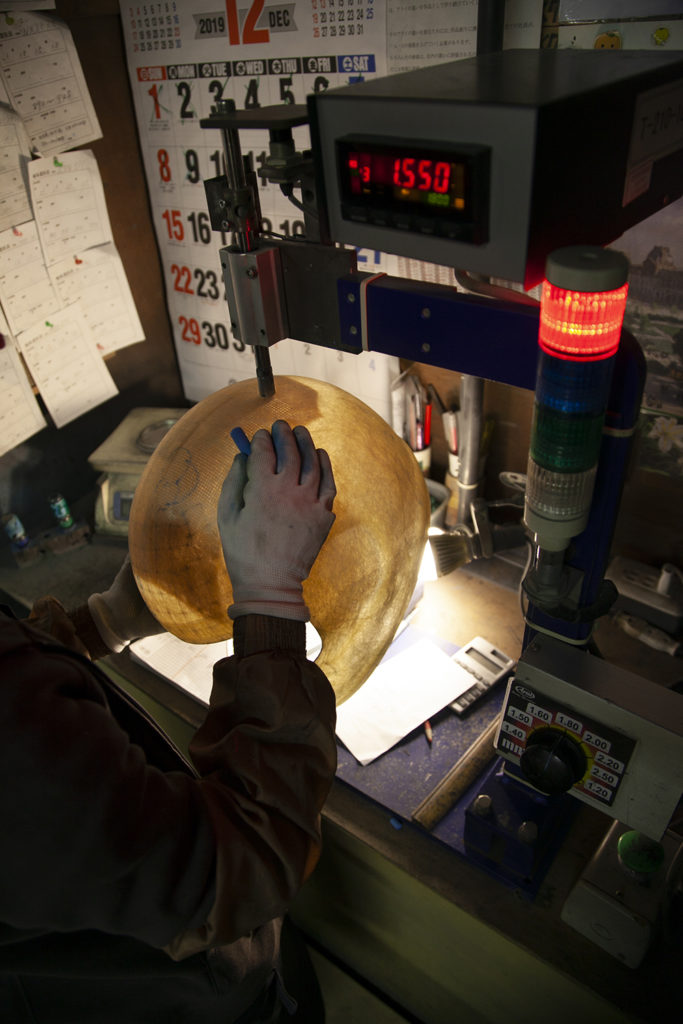

Many other helmet manufacturers and philosophies exist, and riders must make their own conclusions in the knowledge that certification requirements mandated by bodies such as the DOT and ECE only guarantee a minimum standard. Every Arai helmet is still made and inspected by hand at the family-owned factory in Japan; the only automated process is the laser cutting of the eyeports. Over its history Arai has built an enviable reputation for quality and attention to detail. As the saying goes, it is expensive for a reason.

For more information on Arai helmets, visit araiamericas.com.

The post The Why Behind Arai Helmets first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com