“You realize that we’re moving to mandatory evacuation,” the park ranger told me as I pulled up to the campground kiosk to check in. It was August 2020, and Hurricane Isaias was bearing down on the East Coast just as I was about to start my “Adventure of a Lifetime.” The storm was expected to make landfall right where we were standing at North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

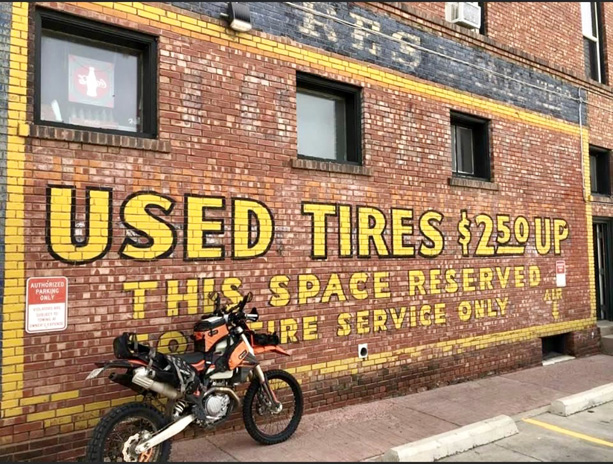

A month earlier, my KTM 500 EXC-F had been loaded on a truck in Louisiana, bound for Outer Banks Harley-Davidson. I had flown into Norfolk, Virginia, with plans to pick up my bike and spend a week at the beach with friends before starting my solo journey on the TransAmerica Trail.

Now I was doing battle with cars and RVs trying to outrun a hurricane. My KTM was overloaded with an expedition’s worth of gear plus a now-pointless beach towel, umbrella, mask, and fins, making it as unwieldy as the rattletrap jalopy of the Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath. I made my way north along the Outer Banks and felt lucky to snag a room at an overpriced roach motel in the ominous-sounding village of Kill Devil Hills.

I had heard that the pavement ended just north of Corolla and from there you could ride on the beach into Virginia, so I got an early start and baptized my knobbies in the Atlantic brine. The plan was to ride west to the Great Dismal Swamp and drop down to Sam Correro’s TransAmerica Trail from there (see “TAT? Which TAT?” sidebar at end of story). It was a gorgeous day in one of America’s most beautiful places – the calm before the storm – and as soon as I was off the beaten track, I thought to myself: I’m doing it. I’m actually riding coast-to-coast on a dirtbike!

I rode west across the causeway to mainland North Carolina where it got really hot, really fast. My riding gear became a soggy wetsuit. I pulled into a state park to re-sort my gear and camp for the night. Just as I entered the parking lot, my bike skidded, and I almost toppled over. My heavy load had pushed the rear fender into the exhaust, melting a strap, which had rolled up into my sprocket, as well as one of the turnsignals and the license plate mount. The state park was closed because of Covid, so after re-shuffling my gear, I was back on tarmac. It was still hot, and black clouds trailed behind me.

Suddenly a bird hit my thigh, bounced into my chest, and flew over my shoulder. Wait, that wasn’t a bird, it was my phone! After a tedious half hour of tacking back and forth down the road, I spotted it – functional but with a cracked screen. When I climbed off the KTM to retrieve it, I felt woozy and was no longer sweating. I held onto a telephone pole to keep from fainting and succumbed to a bout of rib-wracking dry heaves. I was on the verge of a full-on heat stroke. Nearby I saw a kudzu-covered shack that turned out to be a juke joint-cum-country store where I sucked down three Gatorades and laid down over the top of the old-school ice box. Had I not dropped my phone, I wouldn’t have stopped riding and might have died.

Hurricane Isaias caught up with me near Appomattox, Virginia, and I ducked into a gas station overhang to put on my raingear for the first time. It fit rather snuggly over all my off-road gear, and when I tried to swing my leg over the enormous pile of kit on the KTM, I fell over, my legs splayed akimbo with the bike and bags toppling on top of me.

I hadn’t even put a wheel on the TAT yet. Was I in over my head?

A Decision is Made

If I bailed out, I’d still have to get my KTM back home to Louisiana. Shipping it home would be expensive and take a month. The 500 EXC-F is an enduro, the last thing you’d want to ride on the freeway, so I’d have to take little secondary roads back down south. That pretty much sounded like the TAT.

I decided I was unlikely to make it all the way to Oregon as planned. The TAT dipped into central Mississippi, and from there it was only about three hours to my house. The revised plan was to put Oregon out of my mind and just focus on getting home.

Removing the pressure to complete the entire TAT lifted a heavy weight from my shoulders. The storm had passed, and it was a beautiful day with blue skies and cooler temperatures. Virginia is lush and green, and the rain brought out flowers and butterflies. Narrow lanes and gravel roads weaved between red barns and fields of mowed pasture, eventually climbing into cool, dark forests. I could sense the temperature and humidity changes around each dip and turn. I could smell little creeks, pines, and vegetation, the very earth itself.

I veered off the TAT to have a hearty lunch at the Devils Backbone Basecamp Brewpub. With the views, live music, and great weather, I could have spent the day there, but instead I mounted up and crossed the Appalachian Trail and the Blue Ridge Parkway. I stopped briefly at the farm where Cyrus McCormick invented the mechanical reaper that led the United States to feed the world. In the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, I camped in a clearing next to the trail, just me and the bike and a million stars.

Soft Mud Makes a Hard Slog on the TransAmerica Trail

By the time I blazed my way through Virginia, North Carolina, corners of Georgia and Alabama, and into Tennessee, I had perfected my packing and loading system, felt at home behind the bars of my KTM, fought less with my GPS, and really began to enjoy myself.

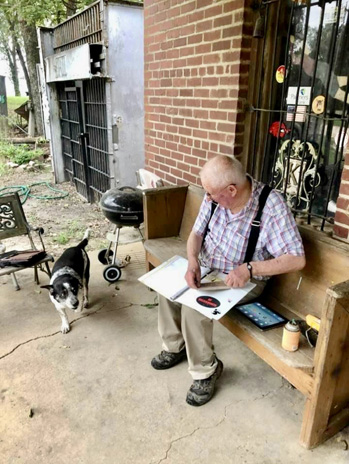

Tennessee was a turning point. Some dear friends rode their Harley down to Lynchburg to join me for dinner and offer encouragement. Just off the trail in Counce, I had breakfast at the home of TAT founder Sam Correro, and he personally adorned my bike with one of his TAT stickers on my front fender. And a buddy in St. Louis contacted me and said he’d meet me in Arkansas so we could ride together for a few days. It was settled: I was back on the TransAmerica Trail to Oregon!

But it wasn’t easy. For many, the hardest part of the TAT east of the Mississippi is the myriad of water crossings in Tennessee. The two worst ones – which you see most often in YouTube videos of TAT-ending epic fails – occur the first 10 miles after you enter the Volunteer State, one right after the other. The gracious host of the motorcycle-friendly Lodge at Tellico lessened my anxiety by sharing some strategies on how to manage them. “Worse comes to worst,” he said, “it’s not too far to hike back here, and I can get ya out.”

In Mississippi, the remnants of Hurricane Marco darkened the skies, and rain turned the TAT into retreat-from-Stalingrad, diaper-full-of-diarrhea sludge. I found refuge in the college town of Oxford, where I checked into a hotel, ordered a steak for dinner, and enjoyed a rest day waiting for things to dry out. But I couldn’t dally because yet another hurricane threatened to make a bad situation worse.

The thing about being in way over your head is that you usually don’t realize it until you’re actually in way over your head. At the southernmost part of the TAT in central Mississippi, I turned down a damp red-dirt road and headed east. The red clay grew more viscous as I followed the ruts others before me had made. In places the muddy track grew wide where folks attempted workarounds to what looked like permanent sludge holes. There came a series of undulating rises through a canopy forest tunnel with the road getting increasingly soupier. I thought about turning back, but it would have been a long detour well off the TAT.

Well, this is where the ‘adventure part’ begins, I thought. Slowly and surely wins the race. Take it easy, stay focused, and we’ll get through this.

One little hill had me spinning my wheel in a red rooster tail of muck going up, then sliding sideways out of control to the bottom, my tires coated like frosting on a Krispy Kreme donut. Now I really had to stick with the trail because there was absolutely no way in hell I could make it back up the slime track I just slid down. I lasted only about a minute more before my KTM became completely stuck up to the rear sprocket. When I dismounted, there was no need for a kickstand because the bike was cemented in place. I walked down the road to scout ahead. Slipping and sliding in my moto boots, each one weighted down by pounds of Mississippi clay, I peered over the rise and saw … more muddy hills, an endless procession of them to the horizon and beyond.

The hot, humid air was thick, and I felt nauseous. I took off my helmet, gloves, jacket, boots, and even my pants and sat down on the side of the road. A black butterfly landed on my bike, then flew over and sat on my knee. We looked at each other for what seemed like an hour. I just sat there, hot and numb. I did not know what to do. Another storm would come that evening – maybe that afternoon – and no way was another vehicle coming down this road. Not today. Maybe not ever.

Thoughts of living the rest of my life in the woods like Grizzly Adams soon dissipated along with my stock of water. Scrolling around on my Garmin, I saw a little spur a few miles back that looked like it might lead to pavement. I stripped the bike of all the gear and scraped off as much clay as I could. With no other choice, I backtracked, dragging the machine sideways over the hills and making multiple trips to retrieve my gear.

Back on blacktop, I stopped at a store and downed a water, a Gatorade, and a Mountain Dew. I was in Bobby Gentry country, and the lyric “Seems like nothin’ ever comes to no good up on Choctaw Ridge” played in my head as I thought that maybe what Billy Joe tossed off the Tallahatchie Bridge was a mud-encrusted KTM.

That night the hotel’s fire alarm went off just as I began a relaxing soak in a hot bath. Guests were summoned to the lobby because the hurricane was kicking up tornadoes in the area.

Was I cursed? Had my karmic debt finally come due?

I took a day to visit Graham KTM, a dealership in Senatobia, and the great guys there changed the oil, adjusted the brakes, and installed a trick tail piece that better supported the weight of my luggage. While they were power-washing pounds of clay off my bike, I asked the shop fellows what strategy locals used to ride those gooey roads. “Man, we never ride in that shit.”

Beyond Big Muddy

Arkansas is a special place. Its mountains are not part of any other continental ridgeline, and the culture – equal parts Southern, Southwestern, and Midwestern – is unique. Ozark people know the TAT, and hospitality and homemade signs of encouragement prevailed along the trail.

In addition to the beautiful vistas and bountiful barbecue, Arkansas highlights included a gentleman who serves TAT riders iced tea from his back porch while photographing the different motorcycles and recording them in his ledger, the little TAT Shak that’s open and free to anyone who wants to stop, and spending a few days riding with Rick Koch, an old college buddy who had come down from St. Louis.

I had no preconceived expectations about Oklahoma, yet it provided some of the best memories of the trip. Intermittent rain and challenging mud made for slow going, and I slid from town to town to take shelter through countryside that I otherwise probably would have blasted though.

I met some of the nicest people of the whole trip, and I visited the little town of Beaver during the World Championship Cow Chip Throwing Contest.

The Way-out West

New Mexico and most of Colorado passed by too quickly. I set back the clock another hour and entered the Pacific watershed after crossing the Great Divide. It was weird to see patches of snow after almost passing out from heat stroke earlier in the trip.

In a little bunkbed bungalow in Sargents, Colorado – a haven for hunters and off-road enthusiasts where I feasted on elk meatloaf – I awoke to shrill whistles and shouts of “yip, yip yip!” Local cowboys were rounding up the herd outside my cabin’s back window.

After weeks of temperatures in the 80s and 90s, it was 30 degrees outside, and I scraped frost off the map pocket of my tankbag. The dip in temperature tripped the aspen trees, and just like that, almost all of them went from pale green to vibrant yellow.

Riding high in the Rockies, I went over Black Sage Pass (9,725 ft), Tomichi Pass (11,962 ft), Los Pinos Pass (10,509 ft), and Slumgullion Pass (11,529 ft) and then zig-zagged down switchbacks into Lake City, said to be the most isolated town in Colorado.

Continuing west to Ouray meant going over Engineer Pass (12,800 ft), which is surrounded by barren tundra that reminded me of the Karakoram Mountains along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

It was freezing cold and extremely windy at the summit, and it was a struggle to keep my loaded bike from falling over as I took off my gloves for a quick selfie. Snow started blowing sideways, and soon it was a complete whiteout. Fog on my goggles turned to frost, and the grade was so steep I was reluctant to move my hands from the handlebars to wipe them. Slinking down the precipice was all the more unnerving because I had to contend with Jeeps and side-by-sides coming the other way. A strip of mud and trickling water on the inside track became gravel-covered ice, forcing me to move closer to the outside ledge.

I never felt comfortable on those steep switchbacks. My bodyweight kept trying to put me over the handlebars, and I couldn’t scoot back because of my loaded luggage. I washed out my front tire on one gravelly switchback, and a passing motorcyclist going up the hill stopped and helped me right things.

After arriving in Ouray, a long soak in the warm mineral waters of the public hot springs was just what I needed to close out an incredible day that featured sunshine, gale-force winds, a blizzard, freezing rain, and more than a few pucker moments.

My Dear Imogene

From Ouray, there were several options. Sam Correro’s route would send me south on the Million Dollar Highway, one of the most beautiful roads in America. Instead, I opted for the more adventurous Yankee Boy Basin route over Imogene Pass (13,114 ft) to Telluride.

The weather the next day was probably the single most beautiful day of the trip. I was in top TAT shape, the bike was running great, and my gear was dialed. The autumn leaves were vibrant, and there were many natural and historic things to see along the way. At one overlook, I met a young guy from California in a new Jeep who had stopped to let some air out of his tires. He was on his honeymoon, and the couple had planned for more than a year to drive this road, which is a bucket-list destination for many off-roaders.

Even though it was a Tuesday in late September, there were a lot of vehicles on the road, especially side-by-sides, not all of which yielded the right of way. One of the trickiest technical bits – a staircase of rock and shale that plummeted down to a precipice below – required a careful study of the approach. The trail devolved into a giant rockface about 100 feet wide that had shale-like “stairs” of varying widths and heights. You must go up the stairs diagonally, pick a shelf to straighten out on, and then go back down diagonally again. On two wheels, this is a feat that requires just the right mix of momentum, balance, skill, and luck to avoid falling off the cliff.

Just as I decided on a route up and hit the gas, two side-by-sides came across from the other direction, forcing me to scramble up the stairs higher than planned. They squeezed by without mishap, tooting and waving as they passed, but I was stuck at the top of the staircase, holding myself to the cliff with just my right leg and about two knobs’ worth of tire. I perched like that for some time, a few Jeeps passing by closely without acknowledgement. When my knees began to shake and I wasn’t sure I could hold on any longer, I launched myself down, kicked off the ledge, and skipped down the stairs, just catching the lip of the trail.

Shaken, I knew backtracking was no longer an option. I was committed to summitting, come hell or high water.

Next I came to a deep, narrow stream filled with softball- to bowling ball-sized rocks. I was at the top of a waterfall that poured into the canyon below. With a cliff on one side and a house-sized boulder on the other, there was no workaround. Before fear got the better of me, I gunned it, and my front wheel skimmed the top of the water toward the far bank. The strong current and slippery, unstable rocks caused me to slip sideways, and I started to fall over, but somehow my boot caught a rock and I bounced back upright as I gassed it over the finish line.

Soaking wet and hyperventilating, it took me awhile to regain my composure. I rode around the big boulder only to find that the little stream I crashed through was but a small tributary of a larger stream that now roared before me. The trail required me to ride up a 6-foot-high steep, mossy waterfall and then hang a sharp left up a switchback. Um…

Remember when I said that you don’t really know you’re in over your head until you’re in over your head? I was stuck between two streams I could not cross. I shut off the bike, took off my helmet, and sat for a long while, feeling demoralized. It was getting dark in the crevasse I was tucked into, and I had to make a decision. It wasn’t like I could establish residency in the shelf between the streams and have my mail forwarded there.

So I put my helmet on and gave it a shot. I closed my eyes and let out a scream as I popped the clutch, laying on a fistful of throttle. The weirdest thing is, I have no further memory of the incident. Suddenly I was on a wide, flat bit of dirt road farther up the summit, out of earshot of the water, but I don’t recall how I got there. It’s like God’s hand reached down and delivered me. One moment I’m crashing into a waterfall, and the next I’m back in my body, calm and relaxed and tootling down the trail, none the worse for wear.

My idyll didn’t last long. In full view of the barren summit, I now faced the final stretch and what for many is the hardest obstacle of the trail. Blocking the final approach to the summit was a large boulder. There looked to be a little ramp around it on dirt, so I took that route, but near the top of the boulder, just around the corner out of view, there appeared a 4-foot ledge. I came to a sudden stop, sliding up on the tank. In trying to turn around on the steep slope, I lost my balance and fell over.

I was above 10,000 feet, short of breath, and my arms felt like wet spaghetti noodles. I was too weak to lift my bike, so I started unloading my gear. Just then, California Honeymoon Jeep Guy came up the trail and said, “Hey, Louisiana KTM Dude!” He put my bags in the back of his Jeep and promised to drop them off at the summit. We then pushed and pulled my bike over the ledge, and I served as spotter for his careful crawl up the face of the boulder.

Near the summit, several vehicles were stacked up at the base of the steepest incline I had ever seen. After Jeep Guy left, I faced another 3-foot stepup to continue on the trail. I was exhausted and again unsure of what to do. The only other bike I had seen was a mangled BMW in the back of a pickup truck.

Just then a side-by-side pulled up next to me, driven by a tour guide. “You look stuck,” he said. “Are you alright?” He told me he was a KTM man himself and that he often enjoyed this trail with his enduro friends. The ledge looked vertical but actually had some angle to it, he said, so the trick was to hit it head on with enough speed to make the next righthand switchback and up the shale slope.

“Don’t worry what line you take or how sloppy it gets,” he said. “Just stay on the gas. Don’t let up. You can do this!”

His enthusiasm was encouraging, and being relieved of my luggage was liberating. After a few false starts, I recommitted and used my “waterfall” technique, screaming as I accelerated into the ledge. When my front tire hit, it lifted straight up into the air. The impact knocked my body back, but I held on with vice grips of adrenaline and gassed it. After going aerial, somehow I touched down where I needed to be.

Maintaining momentum, I threaded around some other vehicles, made a sharp right at speed, and went up into the scree, fishtailing sideways and throwing rocks everywhere, clawing my way up the steep slope. My engine howled wonderfully like I’d never heard before. “Woohoo!” I heard from below, and I thought, I’m doing this! Up and up I went. Just as my front wheel lurched onto flat ground, with my spinning back tire not far behind, the KTM died.

WTF?! How? What? Why?!

My forward movement stopped, and for a moment I was in suspended animation, half on and half off the slope – like Wile E. Coyote when he first runs off the cliff, and then looks down…

Pulling in the clutch, the KTM restarted first pop. But I felt the sickening feeling of going backward. Squeezing the front brake lever just caused the front tire to skid. Locked up and sliding backward, I became disoriented.

Instinctively, I put my right foot down to arrest my slide, but the incline was steeper on that side, and my boot touched nothing. My body shifted to the right, causing me to whiskey-throttle into a sideways wheelie that knocked me backward at an awkward angle. As I landed hard, I felt a crunch below my right knee – what turned out to be a tibial plateau fracture – and I heard my coach shout, “Oh no!” from below.

Within sight of people taking selfies at the Imogene Pass summit sign, the KTM and I tumbled to a halt on the slope, bringing my TransAmerica Trail journey to an end – for now.

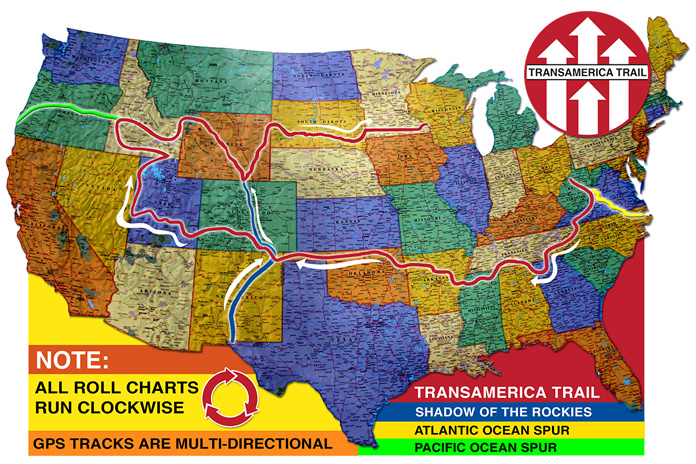

TransAmerica Trail Sidebar: TAT? Which TAT

In the mid-1980s, dual-sport enthusiast Sam Correro began scouting and mapping a mostly off-road trail from Tennessee to Oregon, which he called the TransAmerica Trail. Correro’s TAT now includes a main trail that runs west from West Virginia to Utah, north to Idaho, and then east to Wisconsin. Spurs extend the TAT to the Atlantic, the Pacific, and along the Rockies.

Correro continues to ride the TAT and updates it regularly. At TransAmTrail.com, he sells maps, rolls charts, and GPS tracks. He also provides his phone number and email address to those who order his maps. While on the TAT, I texted Correro to let him know how much fun I was having, and he invited me for breakfast at his home, which is just off the trail in Tennessee.

Another resource is gpsKevinAdventureRides.com, which offers digitized TAT maps as well as GPS tracks. Much of gpsKevin’s main TAT follows the same route as Correro’s, but he offers alternate spurs from Tennessee to New York and from Moab, Utah, to Los Angeles.

Whereas the TAT runs mostly east-to-west, Backcountry Discovery Routes (RideBDR.com) run south-to-north in individual states, and some parts of BDRs in western states overlap with the TAT.

For my trip, I bought maps and GPS tracks from Correro, gpsKevin, and BDR and put together my own trip, mostly following Correro’s route. Since I’m a history buff, I incorporated some of America’s original routes: the Trail of Tears, the Cimarron and Santa Fe Trail, the Mormon Trail, and Lewis and Clark’s Route of Discovery. And as a fan of American culture, I included parts of music trails through the Appalachians and Ozarks and sought out the best local barbecue and regional cuisine.

There are many planning resources available online. Do your homework, prepare yourself and your bike, and go for it! – DS

Listen to our interviews with Dave Scott in the Rider Insider Podcast, Episode 46 and Episode 48.

This article originally appeared in the November 2022 issue of Rider.

The post A Solo Journey on the TransAmerica Trail first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com