We published Dave Scott’s story about riding the TransAmerica Trail from North Carolina to Colorado in our November 2022 Adventure Issue and on our website here, and it ended with an emergency evacuation at 13,000 feet in the San Juan Mountains. This is Part 2. –Ed.

Breaking my leg near 13,114-foot Imogene Pass was probably the best thing that happened to me on the TransAmerica Trail. Had I made it over the summit, I probably would have died falling down the other side. That was my thinking as I cruised into Telluride, Colorado, a year later to resume the TAT where I had left off.

Back in the Saddle on the TransAmerica Trail

After my crash on the TAT, it took six months before I could walk without crutches or a cane. Even a year later, I still had a limp and took stairs slowly. During my convalescence, I had plenty of time to reflect on my TAT experience. Instead of a solo effort like before, I would have my buddy Nathen shadow me in my Jeep and pop-up trailer. We would stay in touch via satellite communicators, and he would be setting up camp and carrying spares, gas, gear, and beer. This would allow me to ride my KTM 500 EXC unencumbered by heavy, hard-to-balance gear.

Since I was laid up in the hospital after my crash with my leg put back together with metal screws and plates, I paid a local guy to recover my KTM from Imogene Pass.

Nearly a year after my fateful tumble, I drove my Jeep and trailer to Grand Junction, where the bike had remained untouched in a friend’s garage. Nathen flew in from Philadelphia, and we loaded the bike into the trailer and drove down to Montrose, where the KTM got an overhaul. Near Telluride, Nathen and I did a shakedown run on Last Dollar Road, an unpaved scenic byway.

The next day, I resumed my TAT journey by riding up to Imogene Pass and a little beyond to the exact spot where I had fallen and ended my first attempt. I had been told that the hardest part of the route to the pass was the 20-mile eastern approach from Ouray. The western approach from Telluride was only about 6 miles; a guy told me his friend did it in a Subaru. I naively figured I’d head up and be back in time for lunch. However, about halfway up, near to the abandoned mining town of Tomboy, the route turned treacherous, and once more, I was pushed to ride beyond my capabilities.

At the time of my crash a year earlier, I was in top TAT shape. I had been on the bike almost two months at that point, having traversed half the continent and crossed over the Great Divide. This time, I was carrying enough hardware in my legs that a hard fall would have it all poking through my skin like a porcupine. Moreover, last time, after surviving one trail atrocity or another, I could say to myself, “Well, I’ll never do that again.” This time I was burdened with the knowledge that I would have to go back down the same way I was going up. If I fell down and broke my leg again – and I almost did! – absolutely no one, not even my mother, would feel sorry for me. I took it all slowly and managed to make it back down to Telluride in one piece.

All Downhill from Here

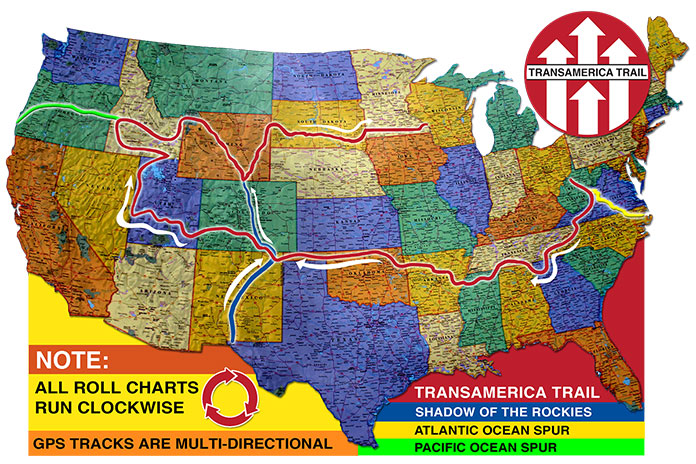

From Imogene Pass back down, I was on the TransAmerica Trail again. I followed GPSKevin’s route from Telluride to Utah, where I rejoined Sam Correro’s route. (See “TAT? Which TAT?” sidebar in the first installment of the TransAmerica Trail story.) The weather was great and the scenery was awesome.

In Utah, just south of Monticello, wishing to avoid the long desert bits that would push the limits of my gas tank’s capacity, I switched over to the Backcountry Discovery Route (BDR), following it all the way through Moab and up the eastern edge of Utah into Wyoming. We set up a series of checkpoints where I would communicate to Nathen whenever I crossed a major road. That way, if I ran into trouble, he’d know where to start looking for me.

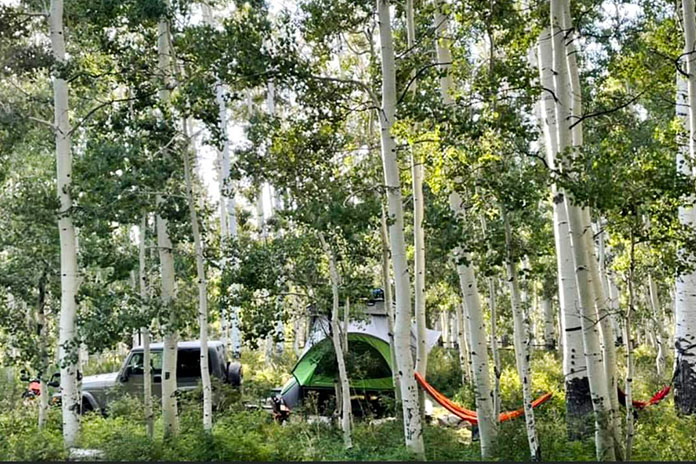

Our first night of camping was at Warner Lake State Campground, which sits at 9,400 feet in the La Sal Mountains near Moab. I was getting reacquainted with my KTM, enjoying its unladen lightness, and having Nathen waiting for me at a prepared campsite with steaks and beer was even better than I imagined it would be.

I had naively thought that once I left Colorado’s San Juan range, the rest of the TAT would be easier. Of course, I was wrong. Many of the BDR sections in Utah require serious enduro skills to get over and through sand, rocks, and steep ledges. Since hitting Moab, I was having three or four near-death experiences a day, and I was starting to get a little PTSD because of it.

I don’t know what guys with those big ol’ Winnebago adventure bikes do when the trail gets so steep that you mostly see just sky out of your peripheral vision while you careen downhill, your gear riding on the small of your back, your feet pressing on the pegs to keep your crotch from shoving the tankbag into the handlebar, feeling that handlebar flex, moving faster than your engine can brake you, when even a glance at the front brake might tuck the front end and the only thing between you and oblivion is a little tap-tap-tap-tap on the rear brake, none of which slows you much when you hit one of those 14-foot switchback drops where you have to do a 180-degree slide turn right at the exact spot where water and gravel collect on that part of the bobsled run.

And if the trail is not solid rock with smaller rocks piled on, it’s sandy shale with 10-inch water ruts running parallel and diagonally down the slope, overlooking a canyon with broken trees and whitewater rapids roaring hundreds of feet below. It’s not if but when you will fall. When you do, Mr. Adventure Bike, if you don’t die or wreck your bike, can you pick it all up and get back on? I’m not talking about lifting the 500-lb beast in your driveway first thing in the morning but rather picking it up on a steep slope of shale, nose-down, in the late afternoon, far from home, when darkness looms and every delay means further loss of light, when your arms feel like wet spaghetti and your knee or ankle is sprained and your ribs hurt when you breathe, which comes out as a gasping wheeze anyway because of the altitude.

Then it’s another trick to get back on that tall-ass bike – and harder still to start it and get going again. Unlike that time in Colorado when I somehow entered a mystical fugue state and glided over some rough patches, in Utah I wasn’t picked up by Charon and ferried across the River Styx.

Out of My Hands

After being so tense for so long, I finally numbed out, held on, and let the bike figure out how to get down the mountain on its own. I accepted that I was probably going to fall every day no matter what. Thankfully, I had good quality body armor, gloves, boots, and helmet, all of which had been tested and held up, even to the point when the bones beneath them gave way.

My denouement arrived when I came face-to-face with a downhill flume that appeared to be made entirely of bowling balls. Partway down the slope, my front tire got stuck between two boulders, leaving me holding everything upright on tippy toes on a third boulder, with the clutch pulled in and about 75 more yards of steep bowling balls to go.

Well, I did my part, was my last thought as I kicked the front tire loose. Gravity and the KTM took me up over a boulder and down into the bowling alley. I hit a big rock head-on, bounced backward, and rolled over it. Then another and another, like bumper cars on a slope, bouncing and hitting and banging my way downhill.

After a long day of nothing but rocks, it was dusk before I made it to camp. When I got there, the tent was set up but nothing else: no food on the barbecue, no cold beer, no smiling face to greet me. Nathen was curled up in his sleeping bag, unconscious. I was frustrated but figured he must have altitude sickness, so it was an MRE for dinner and an early campfire alone.

The next morning was freezing cold, and for the first time, I was not excited to greet the TAT. We were in the Uinta Mountains, in Utah’s panhandle east of Salt Lake City, among 10,000-feet-plus Bald Mountain and Hayden Peak, surrounded by alpine lakes. It was some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve seen anywhere in the world, the air perfumed by pine. I mostly remember that part of the trip like a dream.

The trail moved past towering ridges and undulating high prairie as I crisscrossed between the borders of Utah and Wyoming, ultimately popping down to Bear Lake, where Nathen had already prepared camp. We stayed there for two days to recharge, sleeping most of the second day.

Cousins to the Rescue

As luck would have it, the BDR folks blazed a connecting trail from Utah to its Idaho route that perfectly synched me back up with Correro’s TransAmerica Trail. At Balancing Rock, I left the TAT to follow the original Oregon Trail. One of the highlights of my cross-country journey was tracing the wagon-wheel ruts of America’s pioneers. I navigated my own dirt route to Three Island State Park – a major obstacle for covered wagons in those times – where I picked up Idaho’s state-run Main Oregon Trail Backcountry Byway, a 100-mile dirt route that ends at Bonneville Point.

Nathen and I headed southwest to Melba, Idaho, where my cousins Calvin and Corrina live. We faced double jeopardy: Nathen, who had been listless for days, couldn’t get out of bed, and we had mechanical issues with the Jeep. We took Nathen to urgent care, where he was diagnosed with Lyme disease, usually contracted through a tick bite. I felt bad that I had pushed and prodded him to keep moving; I thought he was just malingering. Nathen flew home to Philly, and I left the Jeep with a mechanic and my trailer with Calvin and Corrina and reconfigured the KTM so I could finish the TAT how I started a year ago: solo and unassisted.

Through Fire and Brimstone to the Sea

The Pacific Ocean Spur of Correro’s TAT skirts the desolate Great Basin, which worried me because of my limited gas range. A full day’s riding took me the farthest I had gone without refueling since leaving Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. When my engine started to sputter dry, I discovered that my fuel bladder was empty after part of it melted on the KTM’s exhaust pipe – fortunately it hadn’t ignited! Luckily, I was already on blacktop coming down from the mountains, so I pulled in the clutch and coasted into a gas station in the little frontier town of Canyon City, Oregon.

With the desert behind me and milder mountains ahead, I faced an obstacle that almost ended my ride. The Devil’s Knob Complex Fire was raging uncontrolled and spreading, and the TAT ran right through the middle of it. I spent the night in a motel near the fire zone and plotted a route farther south toward Crater Lake. However, the fire shifted overnight, and I ended up needing a park ranger escort through a recently burned area. It was sobering to see the melted roadway and burned-up husks of what used to be a forest. The air smelled like charcoal.

The rest of the day was one frustration after another as I navigated my way around the fire. When I got back on pavement, it was dark, and I was almost out of gas. I hit a few miles of Interstate 5, the first freeway I had been on since I started the trip. The experience was surreal. I saw more people than I had in days, sharing three lanes with all sorts of vehicles, the wind from passing semis buffeting my laden dirtbike.

I spent my last night of the TAT at the Wolf Creek Inn. Built in 1883, it’s the oldest continuously operated hotel in the Pacific Northwest – and reputedly one of the most haunted places in Oregon. Arising early the next morning, I was full of energy, ready to embark on the final leg of my trip-of-a-lifetime, the culmination of a two-year journey that started on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean.

A Great Last Day on the TransAmerica Trail

It was a beautiful day amidst magnificent scenery, and I wanted to savor every minute of every mile. I took a little country road excursion to Golden, a well-preserved ghost town, and farther along, after the road turned to dirt, I hoped to blaze a trail down to the TAT. What seemed like a good idea turned out to be a self-inflicted ordeal, and I ended up bushwhacking and nearly succumbing to a hostile blackberry bush.

It was almost noon when I got my last tank of gas. Throughout the entire trip, I had gotten only one flat tire, back in Tennessee. The experience had cost me an entire day, so when I had new tires mounted in Colorado, I had the shop install a bib mousse in the front tire instead of a tube. That puncture-proof doughnut of foam probably prevented multiple flats when I was bouncing from rock to rock like a pinball in Utah. However, at the end of the trail, it went from being merely squishy to downright flat with about 60 more miles to go.

I still needed to traverse the coastal Siskiyou Range, and the trail zigzagged from the treeline down to the Rogue River, then back up and down again, repeatedly. Because of the flat front tire, I kept my speed around 20 mph and took hundreds of turns as square as possible.

Still, it was a great day. The countryside was like a greatest hits album of the whole TAT. Along the Rogue River, the thick deciduous trees reminded me of Appalachia. Climbing into the mountains, the pines, chapparal, and vistas were emblematic of the West. In between were dank, moss-covered redwoods that heralded the Pacific. And I saw more wildlife than on any other stretch of the whole trip: elk, deer, a bear cub, a beaver, and an eagle.

At the rate I was going, it was going to be a stretch to make it to the coast before dark. But somewhere up in the mountains when the road forked, there was a sign in the direction I was going that said “COAST.” That recharged me, but it was hours later before I finally rounded a tree-lined corner and came upon U.S. Route 101. I was met with a cold blast of wind and the open ocean. Just like that the GPS route ended, and the TransAmerica Trail was over.

It was a few miles south on 101 to Port Orford, the most westerly town in the lower 48 states. I hugged the shoulder to ride slow enough to keep my tire together and not get run over. Orford is a fishing entrepot exposed to the rough sea. I found access down to the beach for the ritual dunking of my front wheel in the Pacific, as I had done in the Atlantic when I started my trip more than a year ago.

The wind was strong, the sand was soft, and the tide was coming in quickly. It was all I could do to take off my gloves for a selfie and keep my bike upright. About a foot and a half of water rushed over me, soaking my boots and burying my rims. It was tricky to get out of there, and with that flat front tire, I barely made it back up the eroded slippery cliff to the main road.

I rode back to a dock where there was a little shack that looked like a bar. The cranes were hauling up the last boats of the day as I pulled up to the fisherman’s tavern, leaned my bike against a post, and shut off the engine. That’s when the enormity of the whole thing washed over me.

Stuffing my gloves in my helmet, I pushed open the door, and yelled out the coolest thing ever emitted from my lips: “Hey everybody! I just rode across America on a dirtbike!”

I ordered a mug of beer, a dozen oysters, and a flounder sandwich. After a second beer, when I asked for the check, I was told that one of the other patrons had covered my tab. Later, I was the only guest in a little redwoods lodge, where I watched the sunset from a hot tub, with a bottle of champagne at my side.

Listen to Dave Scott’s unfiltered tale of his entire TAT adventure in Episodes 46, 48, and 50 of the Rider Magazine Insider Podcast.

The post How the West was Won: Finishing the TransAmerica Trail appeared first on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com