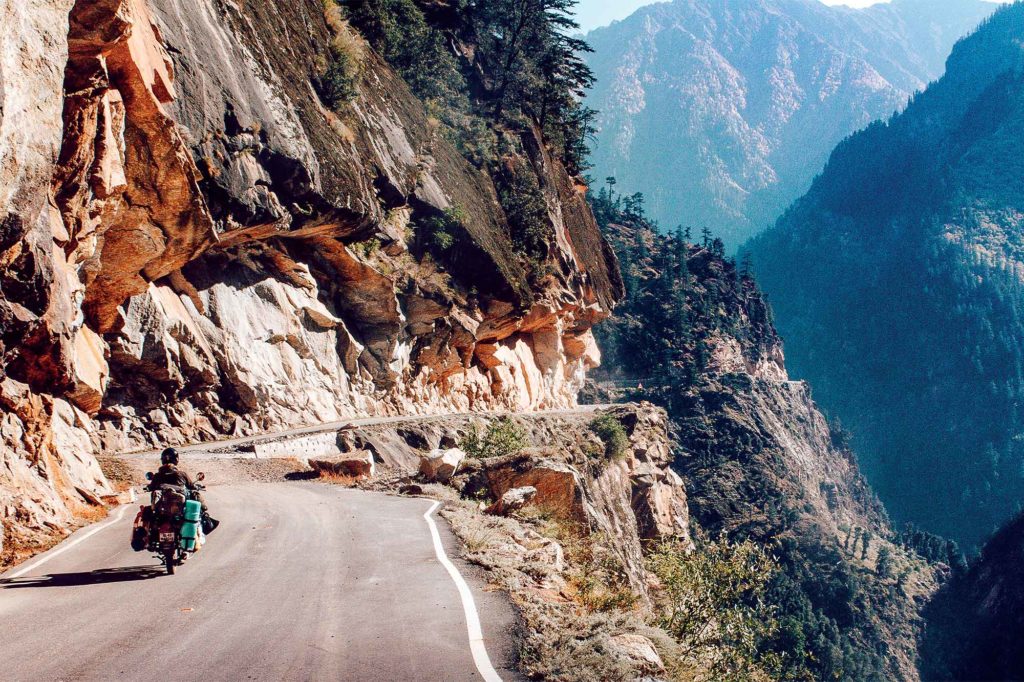

They call it the Cliffhanger. As one of India’s most dangerous and deadly roads, it is a real treat for the experienced motorbike rider. The unpaved route, which is part of National Highway 26, connects two states, joining the towering forests of Kishtwar in the state of Jammu and Kashmir to Killar in the pristine Pangi Valley in Himachal Pradesh. Due to the difficulty and risks involved, this is one of the lesser traveled routes in the Himalayas.

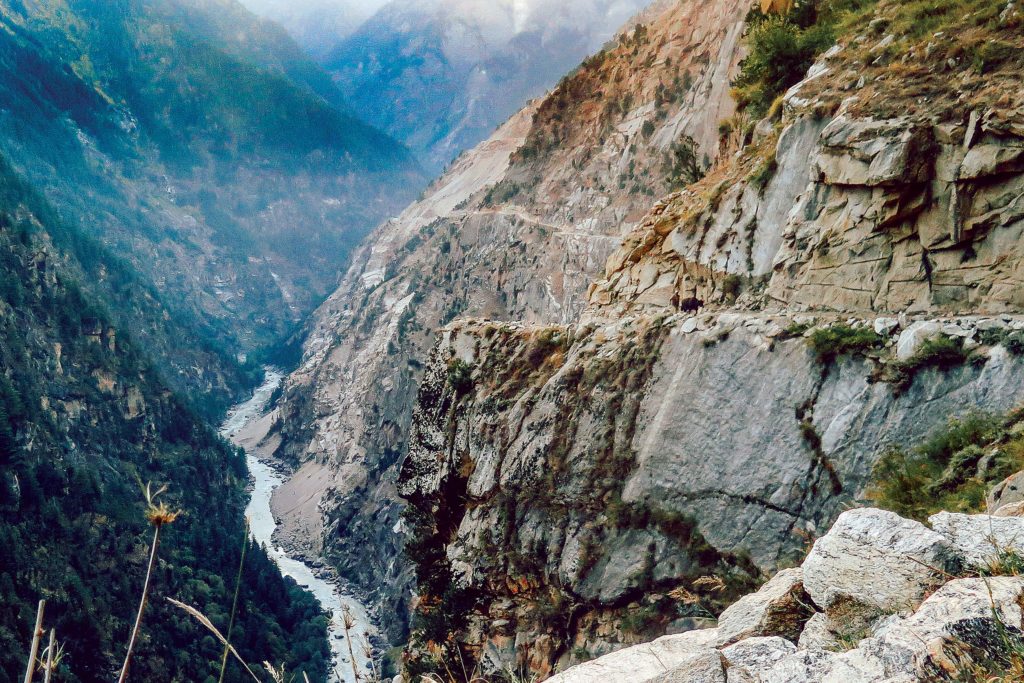

The hazardous, narrow, and spine-chilling road snakes nearly 150 miles around the edge of a steep-walled gorge, much of it hacked out of a stone cliff face, hence its nickname. Through a series of harrowing switchbacks and slopes, the Cliffhanger climbs from 5,374 feet in Kishtwar to 8,091 feet in Killar. A sheer drop on one side could plunge a rider 2,000 feet down into the mighty Chenab River should they make even the smallest of errors. It’s not for the faint of heart.

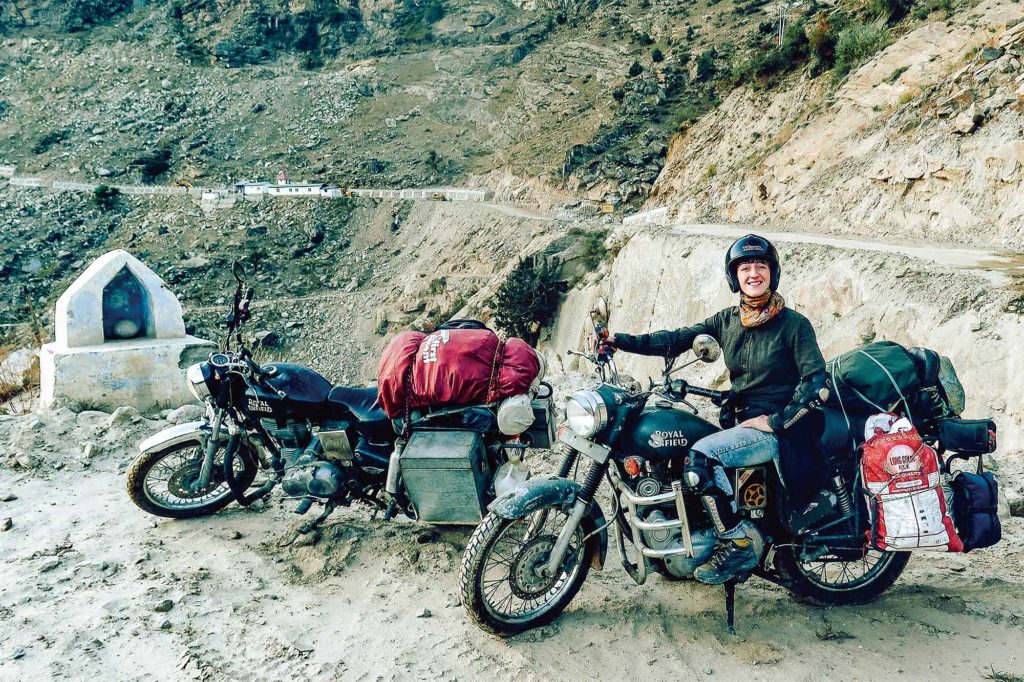

I had already ventured across uniquely difficult roads in Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Himachal Pradesh aboard my 2009 Royal Enfield Machismo 350. Purchased secondhand from a small shop in Goa, I named her Ullu, after Goddess Lakshmi’s steed in Indian mythology, a white owl that she rides into battle.

Ullu and I had been on many journeys together around India and experienced our fair share of breakdowns. She boasted a twice-welded frame, a starter with a mind of its own, and a fondness for breaking tappet rods. A lack of motorcycle mechanics in the backcountry meant a bit of risk, but I was undeterred.

Several of the roads Ullu and I had ridden were touted as the highest passes in not just India but in the entire world, so claimed by bikers in immaculate road gear with selfie-sticks attached to their full-face helmets and stickers affixed to their bikes listing the names of their latest conquests. In my waterproof jacket and Wellington boots, open-face helmet and face scarf, torn jeans and strap-on knee pads, I stood in stark contrast to the other bikers.

Riders I passed on these roads wore leather-clad and armored bike gear that makes them look 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide but when removed, revealed either a tiny, skinny Indian or someone who was, in fact, 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide. In a land of plentiful chapati bread, either is possible.

Though I had done minimal research, I had an idea of what I was about to face. Whispered-about routes discussed over a plate of dal in roadside dhabas are not to be sniffed at. If you follow the breadcrumbs, there are rare rewards to reap.

Interesting hazards presented challenges on my previous trips in northern India, such as metal hooks and nails protruding from the road surface, and thin, silky sand which often whipped up into one’s eyes and robbed tires of grip, snaking across the darkening roads like a subtle cobra, making riders wobble and flounder on steep corners. The lipped edges of most Indian roads I had encountered were uneven and hid all manner of surprises, from barbed wire to broken whiskey bottles, even downed electrical wires.

What unexpected tricks would the Cliffhanger have up its sleeve?

It was the day after my 33rd birthday, and I could think of no better gift to myself than this trip. There is no greater thrill than risking your life on high ledges, of pushing yourself to exhaustion, of handling a heavy machine and guiding her up the dodgiest of inclines, your whole life on your luggage rack, knowing that at any moment a brief loss of focus or a sweaty-gripped mistake could cost you everything.

Given Ullu’s penchant for breakdowns, I promised a bar full of bikers that I would not attempt the Cliffhanger alone. Joining me was my partner, John Gaisford, on his 2012 Royal Enfield Electra, named Pushkarini after the gorgeous stone baths at the edges of many Indian temples.

Having heard so much about this road, I was expecting a little more from the entrance than an idle earthmover and a nondescript road marker. But it turned out that the road, post-monsoon, was under serious construction and cordoned off. Passage was restricted to only one hour, twice a day.

We waited in a dhaba that would, at the end of the road, rob me of two days of riding thanks to some sketchy tap water. We met two other bikers there who fit my earlier description. Their bikes – KTM RC 200 and Yamaha FZ250 sportbikes – were loaded with the latest technology and gear, but it soon became apparent that they had no idea what they were about to attempt.

I suspected that the sports nature of their bikes and street-biased tires made for speed on good roads could cost them dearly on those slippery corners should that famous sand appear. I had seen similar bikes stuck in precarious situations on my journeys through India, usually in the mud. The Machismo, heavy and dependable, had seen me across many a difficult road surface. Though, what its new grippy back tire giveth, the heavily loaded luggage rack taketh away.

John and I rode back to the checkpoint to line up behind a fraying rope with the pristine-looking bikers, who must have thought us quite alien with our well-worn bikes covered in road grit and dust. Someone finally let down the rope, and we cheered. I was the first out of the gate, grinning widely. Being a woman in the lead on the oldest bike in the group is about as empowering as it gets, and I believe it sets an example that women belong on motorcycles.

With the other Himalayan high-pass roads I had ridden, it took time to reach sections that filled me with a sense of impending doom, the catch-your-breath sections, the parts for which I wish I had one of those idiotic head cameras after all, to capture those moments in all their glory. But not the Cliffhanger. It was a lump-in-my-throat challenge right away as my front tire rolled over crumbling rock. A video would never do this road justice.

After five minutes, I was laughing maniacally, calling out to no one that could hear me that I was going to die, my wheels nonsensically guided by shaking hands and a fast-beating heart, which pumped like my Enfield’s engine, loud and roaring. In my mirrors I caught sight of the KTM sliding haphazardly, as predicted, from side to side along the terrain, and I quickly refocused my attention on the broken road.

The drops were something else. You know how when someone tells you that they have been on a high road, and it was steep? When someone says they scaled a sheer cliff face, it is usually exaggerated – or in fact true, but with at least a guardrail or signs around the edges or a lay-by to pull over and take photographs, usually named something romantic like Sunset Point. The Cliffhanger offered no signs, no railings, and no relief.

Whilst trying to get a photo of the cliff, I sat at the edge for a second and knocked a rock with my boot. Seconds later, part of the cliff fell off where my foot had been, and I scrambled back, praying no one had seen me be so foolish. After experiencing this incredible road, falling accidentally off the edge because I could not get the correct angle for a photograph did not seem quite as glorious as plunging to my death atop my Enfield.

The cliff I had been so keen to capture was one of many stunning examples, overhanging, cavernous, and beautifully shaped, with sharp angles and grotesque claw-like edges. Riding through and under these felt like being in a fantasy movie like Labyrinth or Lord of the Rings. Living it was something else entirely.

There was nowhere to stop for a water break, no chadar tents for food. The track was about the width of one 4×4, with few places where it felt reasonably safe to enjoy the mesmerizing view. The temperature was chilly in the shadows, but the sun when overhead burned down on us. We pressed on, doing our best to enjoy the terrain, sometimes hearing the odd scream of frustration or achievement of the other in front or behind.

It was a long day. Eventually the desert-stone rocky paths of the gorge gave way to the lush green pine trees of the valley. As darkness fell, Ullu’s weak headlight did little to illuminate whatever hazards lay ahead.

As the road smoothed out, I stopped alone to switch off the engine and experience the silence all around me. I felt, as is often the case when in the heart of the Himalayas, that I was completely and utterly alone. In our busy world where we long for tranquility, there is no feeling like it.

The road ended as unremarkably as it had begun. The KTM and Yamaha had made it too, and they finally passed us, speeding off into the blackness, with John and me exchanging knowing smiles. Royal Enfield likes to say its bikes are “built like a gun,” and ours had certainly set the standard. I gave Ullu a once-over. Her cracked fork had held out, but the front mudguard had not; the next morning, it would be wrenched off entirely by a surly bunch of local mechanics.

The Cliffhanger had been a test of both rider and bike. I remembered with a smile all the bikers I had met on the way whose suspensions had given out on roads nowhere near as treacherous, making a mental note to treat Ullu to an oil change when we got home, grateful as I was for her. Together, we had beaten the odds.

The Cliffhanger, taxing in effort and mesmerizing in beauty, was a journey by which I will measure every other motorcycle expedition. It was like a roller coaster with just the right amount of thrill but not so much it makes you nauseous. The Cliffhanger left me wanting to do it all over again.

Ellie Cooper is passionate about inspiring other women to ride motorcycles. She taught herself to ride in India, and she has explored the country on her secondhand Royal Enfield. Cooper is the author of Waiting for Mango Season, available now, and she writes for various online publications about travel, adventure, and relationships. You can connect with her on Twitter (@Ellydevicooper) or visit her website EllieCooperBooks.com.

The post Himalayan Cliffhanger | Riding India’s Death Road first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com